The Wild & Crazy Professionals

Bill Miller

(This piece is reconstituted from the presentation at the Rowing History Forum at Mystic Seaport Museum in January, 2003)

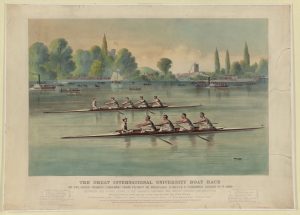

Currier & Ives, Bill Miller Collection

Part 1

If you’re like me, you have a very squeaky clean image of rowing. It is a sport of honor, pure competition, and strong camaraderie. Whether in victory or defeat, you respect your competitor and develop a bond with everyone who rows. Read on and your pristine image will be shattered. In the 19th Century, rowing had a very dark side. Cheating, interference, throwing and fixing races, damaging equipment, poisoning and threats of death were known to occur. The professional rowing crowd in the 1800s would fit right in with the infamous 1919 Chicago “Black Sox”.

The top professional oarsmen were the famous figures of their day. Before baseball caught the public attention, rowing and sculling races were immensely popular. Before the 1850s most races were in work-boats and were between the commercial rowers. Many were the New York Whitehallers who were the taxis of the day. They would row passengers across the East and Hudson Rivers for a fee. Being a faster sculler attracted more fares. Races between them showed professional supremacy.

Some races were between ship’s crews visiting a harbor and local crews. Such was the case in 1824 when the British frigate, Hussar, was moored off Bedloe’s Island in New York Harbor. Captain Harris of the Hussar put up a $1,000 prize and challenged any American crew to a race. It just happened that Captain Harris had on board a fast London-built four-oar and also on board was a hand picked crew of London watermen.

Here’s an account from American Rowing by Robert F. Kelley, 1932:

The New Yorkers immediately turned to the American Star and very shortly had a crew of Whitehall men selected… Final details included the selection of a start off the frigate, one of her guns to call for the start, with the course to and around a boat moored off Hoboken Point and return to the finish at the Battery Flagstaff. By the time of the race, which was held in December, a month hardly associated with rowing in modern times, a good deal more than the original $1,000 was at stake. The entire city was aroused, and early in the morning craft headed out on the river and anchored at advantageous places along the course. Crowds began gathering along the waterfront until 50,000 stood on the wharves and at the Battery. In the early afternoon a sudden burst of cheering among those at the Battery announced that the American Star was shoving off for the race. She was polished and shining, a small American flag flying at her prow. The crew wore special uniforms for the occasion, white guernsey shirts, blue handkerchiefs tied around the head and blue pants. With short, crisp strokes the crew pulled out to the frigate and rested on their oars. Almost immediately the British raceboat, owning the possibly boastful name of Certain Death, was launched. She, too, flew her national colors, and her crew were attired in the British Navy uniform. Captain Harris himself came overside to act as coxswain.

The race must have been something of an anti-climax. At the outset, the American took the lead and clung to it to the finish, the British boat being 300 or 400 yards behind at the finish…

On the night after the race the crews of both boats were called to the stage of the Old Park Theater, attired in their racing costumes, and given an ovation by the audience.

The boat itself, the American Star, became a celebrity. In 1825 the boat was fitted with red carpets and silver oars. The occasion was the visit of General George Washington Lafayette. With a hand-picked crew, the American Star carried the General from Whitehall (New York City) to Jersey City and back. Afterwards, the boat was presented to the General and traveled with him to France. The boat still exists and is preserved at Lafayette’s chateau. Mystic Seaport Museum has a replica named the General Lafayette.

There were two ways an oarsman could profit from a race. One was the prize, usually cash, but sometimes valuable prizes such as sterling silverware, gold watches, and even boats and oars were awarded. One prize is described in the 1873 Aquatic Monthly as a silver championship belt “manufactured by Messrs. Tiffany & Co., in 1864, at a cost of $200. It is of sterling silver, thirty-six inches in diameter, two inches wide, and weighs sixteen ounces. Around it are elegant raised shields, also of solid silver for the purpose of recording each annual contest.”

The second way was the kickback from gamblers. Each oarsman or crew had a committee of supporters or backers that served as managers. They would make all arrangements for a race including raising the cash prize. The backers would then set out to book bets on the race and they would reward their oarsmen for a successful venture. Huge sums of money were bet and many times less than upright people bet more than they could afford to lose. If there was a way to influence the outcome in favor of your sculler or crew then it was tried.

Samuel Crowther wrote in Rowing & Track Athletics in 1905:

Bill Miller Collection

The professional racing drew the crowds and created the public excitement; a race between prominent scullers or crews was witnessed by from ten to fifty thousand people, and the betting was like that on a horse-race. The modern police arrangements were unknown, and the referee seldom decided against the home crew; the patriotism of the small town for its base-ball team is as nothing compared with the feeling in New York for the Biglins or other favorites, and that of the Hudson dwellers for the Wards. In match races each sculler was followed by a pilot barge [usually rowed by eight oarsmen with a passenger in the bow] from the bow of which some friend urged him on and at the same time intimidated the opponent; it was win at any cost. The visiting oarsman had little chance; if the crowd did not break his boat before the start, he would have to run a gantlet of craft as soon as he took the lead, and many a man had his boat cut in two by a barge when leading toward the finish. In one of Ellis Ward’s races on the Harlem against a number of local favorites, he had to dodge four barges that went at full speed for him, and, all else failing, the boats massed at the finish so that he could not cross on the proper side of the stake-boat, and then the opponents claimed that the race should not be given to him because he had not finished in the correct place. It was the universal custom for the leading boat to give the nearest competitor the “wash” and every trick possible was played. The referee was the sole judge, and if he decided a race a draw, no matter what the outcome had been, the bets were off, and there are several recorded cases where such a decision was given simply because the home crew had been heavily backed and had lost.

In 1837 the champion sculler, Stephen Roberts, challenged any man to race in 17 ft. work-boats for $200. Sidney Dorlan of New York accepted the challenge. The race was in New York harbor from Castle Garden to Bedloe’s Island and back. Dorlan won the race and the $200, but Roberts wanted a re-row. Roberts won the re-row and $200. Now the score was one & one and so a third race was scheduled with a $400 prize. Soon after the start Dorlan felt ill with cramps and did not finish the race but Roberts continued and won the prize. A rematch was again scheduled and took place in early 1838. Dorlan led all the way, but near the finish he was run into by a boat containing Roberts’ friends. The referee’s decision was that it was not a race and that it should be re-rowed. Dorlan, who thought he should have been awarded the race, refused to re-row. —- So it goes.

Another tactic used by the unscrupulous backers was to try to influence the betting odds. Faking an illness just prior to a race is one way to boost the odds and make for a bigger pay-out after the unexpected victory, but there were other ways as well.

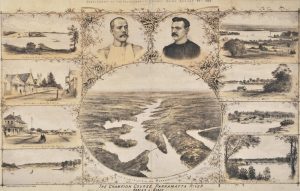

Cleaver wrote in The History Of Rowing about a race between the Australians, Henry Searle and Julius Woolf, on the Parramatta River in 1888:

Woolf had been defeated by Stansbury a fortnight earlier, so he was not much in favor with the betting public, and it looked as if Searle’s backers would have to be content with the bare prize-money. John Spencer [Searle’s manager] refrained from betting at all before the start of the race, and instructed Searle to hang back and “feel” Woolf in the early stages, and, as soon as he was sure of his man, to shake his head from side to side, but not to go to the front until he got a signal from Spencer, who was in a boat following the race.

The race had barely started when Searle’s head was seen to wobble violently. This caused loud laughter among those who had never seen Searle race before. Meanwhile, his commissioners were snapping up every bet offered, with Woolf still leading and going great guns. Suddenly Spencer waved a red handkerchief and in a hundred yards Searle was a length ahead, and the issue beyond doubt.

I think I’d be a bit miffed if I were one of those who jumped into the betting frenzy just after the start only to realize a minute or two later that I’d been duped.

Another example of fair-play (or lack of) and the extent that the participants went to try to protect themselves is described in the 1867 race between James Hamill of Pittsburgh, champion, and Walter Brown of Portland, Maine in Newburgh, NY on the Hudson River.

Again, Samuel Crowther describes the scene in Rowing & Track Athletics:

Four thousand dollars was up as a purse for the five-mile race, and when boats started, it is estimated that some fifty thousand persons were gathered on the banks; and the men were both popular and evenly matched, and the betting was larger than on any previous race in the country. Each sculler had a six-oared barge behind him. In Hamill’s was John Biglin, and Charlie Moore steered for Brown; Biglin and Moore flourished each a pistol, and every moment one or the other was threatening to shoot as the opposing barge happened to come too near the rival sculler. Amid such a volley of curses the two rowed on. Brown was a very fast starter, and he at once took a couple of hundred yards’ lead and attempted to give Hamill a wash, but Hamill, though slow at the start, came up, passed Brown, and reached the stake-boat four lengths ahead. At that time only one stake-boat was provided for a race, and the boat that first reached it had the right of way, and the other man must go around him. Hamill attempted to make a close turn, and the strong ebb-tide took him hard on the boat and he could not get loose. Brown was close behind him, and seeing the predicament, headed directly for Hamill, broke his boat and put Hamill, who could not swim, into the water to be picked up by his pilot. Then Brown went on down and claimed the race; Stephen Roberts, the veteran oarsman, was referee; Brown’s people claimed that no foul had occurred, and, of course, Hamill’s backers asserted their rights. Ellis Ward had been at the turning boat, and he testified while the crowd surged about the officials; to increase the excitement, the dock, on which the crowd stood, fell in, and about half of them went into the water. When all had been calmed, the referee gave the race to Hamill on the foul.

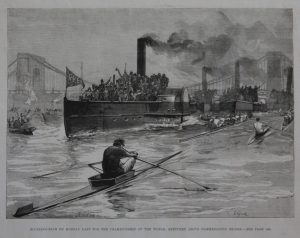

ready to follow their sculler, giving directions and protecting them from interference

1880 Illustrated London News,

Bill Miller Collection

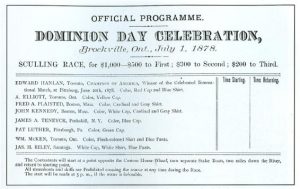

Below is an example of a typical professional race. It was a 4 mile race in Brockville Ontario, July 1st 1878 – $500 for 1st, $300 for 2nd and $200 for 3rd place. Scheduled to race was Ned Hanlan (Toronto), A. Elliott (Toronto), Fred Plaisted (Boston, Mass), John Kennedy (Boston, Mass), James Ten Eyck (Peekskill, NY), Pat Luther (Pittsburgh, Penn), William McKen (Toronto), and James Riley (Saratoga, NY). These were many of the best scullers in America in 1878.

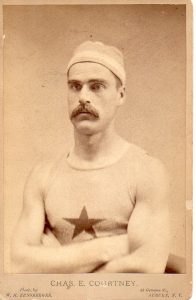

Back in the mid-1800s there was little difference between an amateur and a professional. A professional raced regularly for cash and valuable prizes and made a living doing so. An amateur also raced for the same cash and valuable prizes but was not successful enough to drop his “day job”. An interesting account of this was at the 1873 Saratoga Regatta when an unknown sculler, Charles Courtney, from nearby Union Springs entered the Amateur Singles. He had won a local race in Union Springs and was only noticed by a few Saratoga citizens as being a very fast sculler. He had no difficulty in winning his race and received a nice sterling pot, but he was concerned because he only brought $15 with him and his hotel bill would be much more.

Margaret Look in Courtney, Master Oarsman-Champion Coach quotes Courtney:

“After the race I went up to pay my board, and asked what the bill was. ‘Well, young man,’ said Mr. Moon, ‘come with me into the sitting-room and we’ll settle up.’ We went in and he sat down at a table and pulled out a roll of bills and counted them out. ‘There!’ he said, ‘I won three hundred dollars on this race – you take half of it.’ He insisted upon my taking the money, and he didn’t charge me a cent for the board besides.”

“Then James H. Brister of Union Springs came to my room and said he had placed a little on the race and as I had done all the work I ought to have a share in the result. He had won six hundred dollars and gave me half of it. I felt like a Rothschild. I never had so much money before. I left Saratoga with $450 in my pocket, besides the fifteen dollars I had brought. I tell you, I never let go of that money until I got home.”

So, the Saratoga Amateur Champion took home over a year’s worth of wages for his success in the race.

Part 2

Rowing’s Popularity

Perhaps it is worth taking a look at the popularity of 19th Century rowing. Competition between watermen became very popular with the public soon after the formation of the republic where tens of thousands of people earned their livelihood propelling watercraft with oars. From fishermen and whalers to pilot gigs and life-savers, from naval frigate tenders and harbor ferries to Whitehall taxis and ships’ provisioners, many people pulled an oar for a livelihood. This led to contests, although fairly disorganized, and caught the public’s attention and interest. With this attention and interest grew the opportunity to make a quick dollar by betting on the outcome. This was the fuel that fed the popularity fire and through the first half of the 1800s larger and larger crowds were drawn to the match races.

The Civil War checked the growth because of its consuming demand for manpower and energy, but soon after the war’s conclusion, the public’s interest grew with tremendous enthusiasm. Maybe the single most notable event occurred in 1869 when Harvard sent a letter of challenge to both Oxford and Cambridge to a race on the Thames. Cambridge declined but Oxford accepted. The race to be in coxed-fours on the Putney-to-Mortlake course (4¼ miles).

In July, Harvard made passage to London bringing with them: their manager, own cook, boat-builder (Elliott of Greenpoint, NY), three racing shells, 50 newspaper correspondents, and numerous Harvard officials and supporters. After arriving in London four more shells were offered to the Harvard crew. In the end, a shell Elliott brought over from New York in pieces, was assembled and used in the race.

The Harvard accommodations were at the White House on the embankment and daily drew dozens of visitors and hundreds of spectators. It wasn’t long before the Harvard men realized that this was going to be a huge public event and that they needed to take precautions to ensure that nothing foul occurred.

The Harper’s Monthly of December, 1869 gives a very good description of all the preparations for the race:

The two chief dangers that seemed to threaten our men from outside sources were, tampering with what they ate or drank before, and interference in the race itself. The former was guarded against with great care for ten days beforehand, by having a double allowance of food and drink coming into the house, one through regular channels, the other by secret means and the hands of Harvard men only. Though the suspicion was day by day materially reduced, the feeling still was that we should be very much chagrined if drugging the food, or any thing else in our power to foresee, was not prevented. The men with whom we were to row, or their friends, we never thought of mistrusting. It was only the tools of betting men whom we had reason to fear.

Meanwhile back in the States, many communities followed the race preparations with keen interest. Some even went so far as to plan celebrations should the Harvard crew win.

The H Book Of Harvard Athletics by J.A. Blanchard describes:

The New York City Hall had been decorated with flags in anticipation of victory, and they had prepared to fire one hundred guns to celebrate the defeat of England. Harvard for once was the great popular American University, representing the entire country, and her crew was looked on with enthusiasm even in its defeat.

The Aquatic Monthly of July, 1872 states:

In the city of Milwaukee preparations were instituted for a grand pow-wow in case the American crew should be victorious. A public meeting was called at the City Hall, a salute of fifty guns was to be fired, and the ringing of bells and blazing of bondfires, were to add their effects to the general rejoicing.

The race was a great one. The London Times reported one million spectators on the banks of the Thames. Harvard led for the first two miles and then Oxford gradually drew ahead.

Rowing & Track Athletics describes the scene:

At Barnes Bridge, five furlongs from the finish, two lengths of clear water separate them. For miles back the dense mass on shore has been swaying and struggling, and now, like a mighty river, is sweeping on over fields and fences, ditches and hedges, wild, mad with fierce excitement, yelling at every breath, and with all its might. Seven hundred and fifty thousand people are said to have been there that day. Never, but once in this generation, has such a crowd been seen in England, and then when the Prince of Wales first brought his wife home. The Derby Day can not compare. All previous water fetes sink into insignificance.

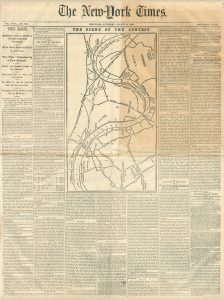

Aug. 28, Bill Miller Collection

The fifty American correspondents pounded out their stories for the American press to be telegraphed across the Atlantic. The New York Times filled nearly their entire front page with the story including a map of the course. This was the thrilla on the Thames.

Within months all across America, hundreds of boat clubs were founded. Dozens of colleges formed rowing clubs. Rowing races, boxing matches, and horse races were the most popular events in the country. College races and sculling matches were more popular than ever. The professional scullers became the super-stars. Lurking at these events were the gamblers, ready to take money from the public any way they could.

Part 3

A Colorful Toronto Sculler Becomes World Champion

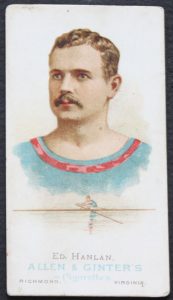

On an island in Toronto Bay lived a family who owned and operated a hotel. The innkeeper’s son would soon become the superstar athlete similar to what we see today at the highest level in professional sports. His name was Edward “Ned” Hanlan. His first press came in 1860 when, at the age of 5 years, the Toronto Colonist wrote about his rowing across Toronto Bay. This would be the first of thousands of inches of print written about the sculler who would be known as The Boy In Blue.

In 1876, he won some local regattas with ease and attracted the attention of a few money men. Twenty men, such as Colonel A.D. Shaw, the American consul, formed the Hanlan Club. These were Ned Hanlan’s advisors and business managers making race contracts, arranging for prize money and essentially promoting and cashing in on his success.

At the 1876 Centennial Regatta in Philadelphia, Hanlan decided to test his skills in the Professional Sculling Championship. It was rumored that he had to make a hasty exit from Toronto because of a minor scrape with the local police. In Philadelphia, some of the best scullers in the United States had entered and little attention was given to the Canadian. It would be the last time that his name would be mentioned without igniting a fierce discussion about his prowess.

The race is described in The Canadians-Ned Hanlan by Frank Cosentino:

Only 21 years old and entered in his first international competition, Hanlan delighted his fans by winning his first heat. But it was the race of the second heat, against the American contenders Fred Plaisted and Pat Luther which amazed the crowds and made Ned Hanlan the center of attraction. During the race, Hanlan actually stopped rowing and peered ahead. He would allow the American to creep up even with his stern and then accelerate with a long, powerful stroke, leaving Plaisted huffing and puffing and thoroughly incensed as the crowds cheered in amazement.

In many of the newspaper accounts of his races to follow, his long, smooth and powerful stroke was described as it is above. He was also referred to as the master of the sliding seat, a new invention introduced a few years earlier. His style, rhythm, length and power allowed him to win many of his races with ease. But not all races were to his liking.

On July 5th, 1877 a Boston newspaper described the professional scullers’ race at the July Fourth Regatta with 30,000 spectators at the edge of the Charles River:

The Race Of The Day in which the greatest attention seemed to be centered was that for the single-sculls wherries. The entries for this race embraced many of the finest professional scullers in the country. The distance was 2 miles with a turn and the prizes were $150, $50, and $25 respectively. Entries were, in order of starting position: Fred Plaisted, James A. TenEyck, Alexander Braley, James Kelly, Frenchy Johnson, John McKeel, M.J. Ahern, Edward Hanlan, D.D. Driscoll of Lowell, William McCann, P. Driscoll, and George Hosmer. As the scullers took their position Hanlan seemed either at a loss to know where he belonged, or inclined to fish for a better boat position. He was finally assigned next to Frenchy Johnson.

All took the water together at 5:37 PM. After proceeding about a dozen lengths, Plaisted shot to the front, closely followed by TenEyck and McKeel, while Johnson, DD Driscoll, Hanlan and Hosmer were working hard to get an advantage over each other. After pulling about a quarter mile it was evident that Hanlan and Johnson would surely foul, and they did finally, just at the very time Johnson seemed to be crawling up on Plaisted. Johnson was leading Hanlan slightly when it happened, but which of the two was to blame could not be definitely ascertained, although each laid the responsibility on the other. Both straightened out after about 10 seconds of time and the race from here to the stake was close between them, Johnson having rather the best of the Toronto champion, although Plaisted continued to lead. What transpired among some of the scullers at the upper stake was quite exciting.

Plaisted made the mile in 6 min. 20 seconds, just three lengths ahead of Johnson and had squared away for home when Hanlan was nearing the stake. The latter, either with intent or not knowing he should turn the stake from the right to left, got directly in Plaisted’s way, whereupon Plaisted yelled out to the judges: “See what that man intends to do to me!” meaning Hanlan. Mr. Fitzgerald, one of the judges, cautioned Hanlan to get out of the way, adding “You have done that on purpose,” whereupon Hanlan replied in a manner that was exceedingly unbecoming, and continuing his course struck Plaisted’s boat with such force that at first it was thought the latter would have to give up the race. During this time Johnson had been delayed at the stake and was waiting with TenEyck and Driscoll at his side Hanlan ran into him also. Frenchy called the attention of the judges to the fact. The boats laid still for several seconds, with McKeel, Hosmer, Braley and Ahearn awaiting a favorable chance to turn, and all again got under way after Hanlan, who had been lying abreast of the stake, was told to pull home by the judges. The struggle home for first place was terrific, each man pulling all he knew how. Frenchy, who was second, in his eagerness to win, rowed very close to the stone wall after leaving the sluice, and had it not been for the crowds along the wall, would have run into it. All came down in good style, Plaisted crossing the line about a length ahead of Johnson, with TenEyck third, DD Driscoll fourth, McKeel fifth, Hosmer sixth, Hanlan seventh and the rest close upon one another.

Hanlan claimed a foul after the race and the judges met at the Union Boat Club for a hearing. The judges decided that the foul was the fault of Hanlan.

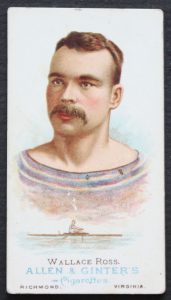

However, most of Hanlan’s races went like his race with Wallace Ross in Toronto Bay. Hanlan met the rising star from Saint John, New Brunswick in October for $300 per side. The public eagerly followed each day’s training by both scullers. Betting was fierce with the New Brunswick public betting as high as 10:1 in favor of Ross while the Toronto bookmakers snatched their bets. On October 16th, after a weather delay, the scullers took to the water. Twenty-five thousand spectators gathered for the race.

Again, The Canadians-Ned Hanlan describes the scene:

Hanlan and Ross were in their respective quarters when word came that the race would be rowed that day. When Wallace Ross walked out to take his place in his boat, polite applause greeted him. When Hanlan appeared, wearing his traditional blue shirt, a loud and sustained cheer arose from the waiting crowd, getting louder and longer with each step he took. There was no question who was the favorite, the pride of the town…

At the start, Hanlan opened a good lead. The two oarsmen were a contrast in style: Hanlan with his long, smooth, loping sweep of the oars gliding ahead; Ross with his short, choppy, slapping effort lurching forward with every pull of the oars. When Hanlan began to steer off course, Ross was able to catch up. But Hanlan soon corrected his error and used his powerful sweeping stroke to spurt ahead by six lengths. Again he started to steer far out of his lane, while shouts of “stop” and “back in” rose above the din of cheering. Hanlan stopped, looked around, saw his mistake and turned back to the course.

Back in his proper lane, Hanlan was drawing farther ahead with each dip of his oars. At the turn, four kilometres up the course, he had opened up a gap of 10 lengths. Once around the turn and headed toward the finish line, Hanlan stopped and looked around, first to see where Ross was, then to survey the huge throng milling on the shore and cheering from packed decks of the steamers. A roar went up from the crowd. Then while Ross went by, heading for the turning buoys, Hanlan acknowledged the cheering, kissing his hand three times to the crowd, and started to row again. Each section of the huge crowd roared its approval as Hanlan came into view. Ross seemed disheartened and fell farther and farther behind, while The Boy In Blue alternated between stroking powerfully and acknowledging the cries of the crowd. Soon he was 20 lengths ahead, and by the end of the race, Ned Hanlan coasted to the finish line 30 boat lengths in the lead.

For the New Brunswick public, it was a bitter defeat… Toronto gloried in the victory.

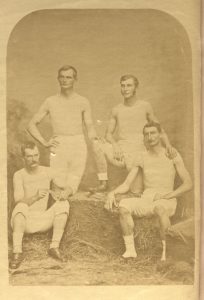

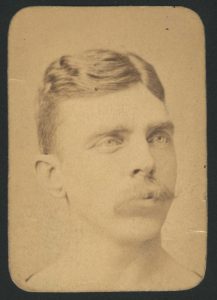

Allen & Ginter Cigarettes

premium cards,

Bill MillerCollection

Meanwhile, the other great sculling figure, Charles Courtney, was capturing every amateur championship around. He went on to an undefeated amateur record of 88 victories without a defeat. At the same 1876 Centennial Regatta, Courtney won the Amateur Sculling Championship event, while Hanlan won the professional event. Courtney turned professional in 1877 and in July he encountered one of his first distasteful (literally & figuratively) experiences in the professional sculling ranks.

On Greenwood Lake, New Jersey, Charles Courtney and Saratoga sculler, James Riley, were preparing for their professional sculling match.

In Courtney, Master Oarsman–Champion Coach, Margaret Look describes the events:

“Up to noon today Courtney was in magnificent condition. He said he never felt so well before a race in his life. Three or four of his intimate friends and backers were at the little hotel with him, keeping a close guard over his interests,” the Ithaca reporter wrote.

“They all sat down to dinner together at 12:00 o’clock, and Courtney ate a hearty meal, the principal dish being mutton. After dinner he called the waiter girl and said that he would like a glass of ice tea. All his friends agree that the hotel proprietor, Mr. George, stopped the girl, saying that she did not know how to make it, and that he would make it himself. He did so, and handed the mixture to Courtney, who drank only part of it, saying, ‘That’s the worst tea I ever drank.’ A moment afterward he said, ‘I feel very bad.’ And rising from his chair, vomited his entire dinner.”

Courtney immediately fell into a state of collapse and had to be assisted upstairs and put to bed. A fierce pain attacked him in the pit of the stomach and gradually a burning sensation mounted to his throat, remaining there. His hands and feet became cold and clammy, tears ran from his bloodshot eyes, and a cold perspiration broke out on his forehead. Finally he fell into a complete stupor, from which it was impossible to rouse him, even with vigorous shaking. This description was in the special dispatch to the New York Times.

Messengers had been sent for physicians and medicine, but it was two hours before Dr. Olcott, who lived across the lake, arrived. One of the afternoon trains brought Dr. Ward of Newark, New Jersey and Dr. Nicholas of New York, who were pressed into service immediately. Their treatments were a huge mustard plaster on his stomach and chest, some camphor, brandy and water and paragoric. He did not rally, however, for a long time.

A steady stream of anxious people gathered in the hotel and filled the staircase leading to Courtney’s room, but only a few were admitted to his room, one of them being Riley. When he saw his big, muscular opponent writhing in pain, Riley said, “This man is sick, and I will not row him. I want a well man to row with, and we will postpone it until Monday or later.”

Then Riley went downstairs, where he was met by some of his friends and backers. One of them, Oliver Johnson, in a loud-mouthed manner, said, “Let the sucker come down and row you,” going on to say that Courtney’s sickness was a sham…”

Frank Brown, the referee, decided in favor of Riley and announced that the race would be rowed at 6:30. Courtney could not show and the race and purse was awarded to Riley. —- So it goes.

It didn’t take very long for the Courtney backers and the Hanlan Club to arrange for the clash of the two sculling titans. A race at Lachine, Quebec was set for October 3rd, 1877 with a prize of $10,000.

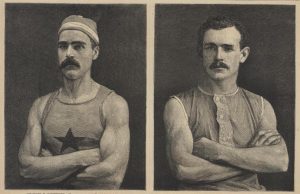

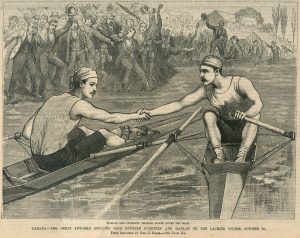

Harper’s Weekly, Oct.12, 1878

Again, we go to Margaret Look in Courtney, Master Oarsman–Champion Coach:

Train after train had brought in an estimated 20,000 visitors. Flags were flying at the quarters of the contestants, vendors followed the crowds to the shore line and to every vantage point along the river. After the storm and other delays, at 4:15 the steamer finally gave four whistles, the signal for the contestants to appear.

Hanlan was the first to come to the starting point. He wore a blue shirt with red trimming, and a red cap. He was followed by Courtney who had on a white shirt with the blue star in the front and a sky blue cap. Both men had heavy, dark mustaches, popular in that era.

They dipped sculls together, Hanlan pulling 31 strokes a minute and Courtney 38. The lead, always slim, changed hands several times, with the pace seeming to get faster and faster, as the two shells sped “fairly hissing through the water.” The cheers from the spectators were deafening.

There are several versions of what happened as the men reached the last two thirds of a mile of the course. One account said that Hanlan spurted ahead by three boat lengths, then Courtney pulled harder and faster and kept gaining on Hanlan. There was still time for Courtney to win, but some obstacles, said to be barges, had drifted into the lanes. Both oarsmen had to change course to avoid them. Hanlan paused and Courtney paused, too, but longer. Hence Hanlan won the race by a boat length and a quarter…

The debate over fairness of the race, the possibility of foul play and the chance that it may have been “sold” continued in both countries.

1978 Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News

The legitimacy of the race was never resolved and a great opportunity to promote an even bigger race was presented. Mr. A T Soule of Rochester, proprietor of the Hops Bitters Manufacturing Company, offered $6,000 to the winner of a new match between Hanlan and Courtney to be raced on Lake Chautauqua in Mayville, New York. A 5-mile race with turn was set for October 6, 1879. The town of Mayville began preparations. Construction of a grandstand for 50,000 spectators was begun. A railroad spur was laid along the shore so that an observation train over one-half mile long could follow the race.

As race day approached 25,000 spectators arrived the day before the race, but the race was postponed to October 16th because Hanlan’s boat broke. The spectators decided to stay and wait there the extra ten days. The crowds grew and grew for the event on the 16th. Accommodations and facilities were stressed and anticipation grew with each passing day.

Courtney, Master Oarsman–Champion Coach describes the scene:

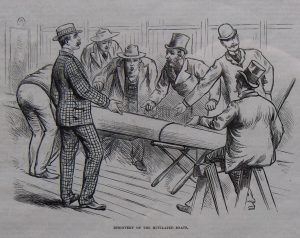

The morning of the 16th found Jamestown almost a ghost town, because everyone was on his way to the northern end of the lake. Storekeepers [in Mayville] were just opening their doors, and the hotel kitchens were getting breakfast ready, when rumors spread that during the night Courtney’s boats had been sawed in two.

Speculation was rampant. Who had sawed the boats? Would the race be rowed? What of the bets that had been made? Mayville was in an uproar.

When two Jamestown reporters went to Courtney’s headquarters at the Cornell residence, Courtney said, “Boys, they sawed my boats in two. Then he explained that he was awakened at 5:30 that morning by Bob Larmon, his nephew, and Burt Brown, both of them amateur oarsmen, who had been hired to help with the boats. These two men had told Courtney that they left the boathouse at 6:00 o’clock the evening before to go to Mayville for supper and on an errand. When they left they locked the boathouse door on the lake side with a padlock and hooked the rear door, then put a nail over the hook. When they returned from Mayville, they found the rear door had been forced, the nail broken, and both boats cut in two. The racing shell was sawed nearly through, in diagonal direction 12’ 10″ from the bow. The practice shell was sawed entirely through 6’4” from the stern.

1879 Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News,

Thomas E Weil Collection

Courtney told reporters that he had told Blaikie [referee] the week before about the offers he had received to fix the race. He also said his life had been threatened, and for this reason he had been carrying a gun the last few days. Courtney showed reporters some of the threatening notes he had received. One was signed “Jack and Jill,” and the other bore the name “Justess.”

The little community of Mayville had never seen such “sharpies” before. “Every swindle known to dishonesty was practiced with impunity at Mayville,” the Jamestown reporter wrote. The Syracuse Courier said, “The developments of today created a feeling of widespread disgust, the result of which will be to discourage public attention in future sporting events….” Other papers echoed this feeling, saying that the real victims were the spectators who had no way of knowing whether a competition was honest or not, but now would probably consider all contests crooked. They predicted a quick demise for many spectator sports. The editor of the Troy Times, Charles S. Francis who was a skilled sculler and Cornellian said: “It seems as if never since the firing on Fort Sumter did an event so arouse the anger of the American people. In every city, village and hamlet, wherever a telegraph wire or a newspaper penetrated, the storm of indignation raged.”

Yes, the suspicion of fixing and manipulating races was strong and widespread. Especially since the Mayville fiasco came soon after the Riley Affair.

The book, The Canadians–Ned Hanlan describes this race:

The Town of Barrie [Canada] was holding its second annual regatta on Kempenfeldt Bay and had invited an American, James H. Riley, to row against Hanlan. The champion [Hanlan] had agreed, against his better judgement. He was not in good condition after his recent trip across the Atlantic, and halfway through the course Hanlan had to stop. Riley was stunned and refused to cross the finish line. He had obviously placed bets on Hanlan and would lose his money if he won the race. The judges were flabbergasted by the whole affair, ruled the race a draw and ordered a re-row. Hanlan declined, preferring to forfeit the prize money.

Ned Hanlan was a colorful personality. Pleasing the crowd was important to him. He felt a little showboating would play well with the spectators even when huge sums of money were at stake. In November of 1880, Hanlan was matched against the World Champion, Edward Trickett from Australia. The race was set for the Thames in London. Hanlan was tremendously successful in North America and the Trickett race was his opportunity to become World Champion and a lot of people could make a lot of money with his victory.

We go to The Canadians–Ned Hanlan again:

The Hanlan-Trickett race was the most discussed and anticipated rowing championship ever held to that time. From Australia, bookmakers received an estimated $100,000 in bets. The difference in size between the two oarsmen was enough to attract large sums from the Antipods [Hanlan 5’ 8″-150 lb and Trickett 6’ 5″-195 lb]. Hanlan’s undaunted supporters eagerly countered all wagers on Trickett. On one day alone, $20,000 was wired from New York in support of the North American champion. In Toronto, the betting on the native son was so intense that one of Hanlan’s advisors, Mr. H.P. Good, organized a group wager. Two days before the race a line-up two blocks long trailed down Yonge Street from the Bank of Montreal offices. Approximately $42,000 was raised and wired to England to back The Boy In Blue. For every Canadian and American dollar, however, there was an eager Australian or Englishman ready to match it. But odds, which had been very much in favor of Trickett when the race was announced, began to even out as the November 15 event approached.

Champion of the World, Allen & Ginter cig card,

Bill Miller Collection

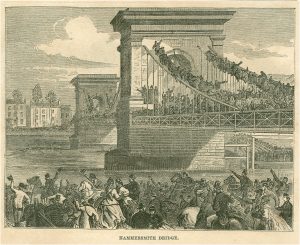

Race day dawned damp and murky. Showers fell but failed to dampen the enthusiasm of the British public. Along the shores or watching from one of the bridges which crossed the river, an estimated 100,000 people.

In some ways, the November 15 race was a study in gamesmanship. Hanlan seemed so completely oblivious to any pressures. Aware that the Governor-General of Canada had requested that news of the race be telegraphed to him immediately and that newspapers from coast to coast were writing of this race as an event of national importance, Hanlan simply said, “I can assure you that I will do my best, not only for myself and friends but for the honour of the country across the water, which I love so well.”

At 12:30, the starter’s signal was followed by four splashes of water and a deafening cheer from the spectators. The race was on. Trickett, relying on a shorter stroke and the power of his immense arms, started with 40 strokes per minute to Hanlan’s 36. His slight lead at the beginning was quickly wiped out as the full force of Hanlan’s stroke took effect. Reaching the Soapworks, a landmark one and a half kilometres beyond the start, Hanlan’s steady stroke had opened a lead of two lengths, and the pace was such that Trickett seemed to be straining to maintain his arm-wearying tempo. A cheer went up from the huge crowd. Hanlan seemed to enjoy his reception so much that he steered off the course. Anxious shouts filled the air, until, with one hard pull of his left oar, he was back on course, still two lengths ahead of Trickett.

At Hammersmith Bridge, about one-third of the way down the course, Hanlan had opened up a three-length lead. On the bridge above the oarsmen, an ecstatic jumble of people clambered from one side to the other in their attempt to get the best view. The cheering which had been continuous ever since the oarsmen came into view abruptly stopped and was replaced by a murmur of puzzled speculation. Hanlan had stopped rowing! Trickett, sensing that something had happened, turned, saw the gliding Hanlan boat and set out to close the gap. Pulling even with his contender, the Australian watched in dismay as Hanlan picked up his pace and again spurted into a three-length lead. The spectators along the shore and above the bridge shouted their appreciation for Hanlan’s prowess. The outburst was even louder when Hanlan let his boat drift near the bank and nodded his head to the delighted spectators. Between Hammersmith Bridge and Chiswick, about half-way down the course, Hanlan stopped rowing, leaned back and calmly surveyed the scene. Trickett relentlessly rowed on. Pulling even with Hanlan’s boat again, Trickett watched in disbelief as his opponent, with a few powerful strokes, re-established his three-length lead. About 15 minutes into the race, Hanlan spotted William Elliot, whom he had defeated for the English championship the year before, watching from a boat. Without hesitation, Hanlan rowed over towards him, asked how he had spent the year and generally caught up on what had happened since their last meeting. By this time, the crowd was in a frenzy, and Trickett was straining to take the lead. His conversation finished, Hanlan leaned overboard, scooped up a handful of water and wet his face and powerfully made his way back into his race lane. As he approached the Bull’s Head Hotel, the headquarters of the Canadian contingent, Hanlan stopped, removed his handkerchief and waved it to the spectators. He seemed to be reserving one item of conversation for each group of spectators along the course.

With one and a half kilometres to go, Hanlan had again opened up a three-length lead. Trickett was obviously beaten. He had rowed steadily from the beginning, unable to take advantage of any rests and forced to sprint against his will when it looked as if Hanlan were in trouble. The all-out cheering which accompanies a tight contest had died down. Though those who had bet on Hanlan were still urging him on, those who had bet on the Australian seemed resigned to their loss and only occasionally raised their voices in more of a plea than a cheer.

Suddenly, the cheerers pleaded and the pleaders cheered. Hanlan appeared to collapse. He had slumped forward, his oars drifting, his boat slowing down under the burden of his weight and drag of the oars. Trickett turned to see his competitor and, filled with new hope, began to pull harder. Nothing like it had ever been seen on the Thames. The challenger in the lead was seemingly helpless, as the champion, arm-weary from the constant strain, sought to regain the lead and his title. All around sounded the confused din of thousands who couldn’t believe what was happening. As Trickett pulled even with Hanlan, he cast a glance over to the motionless challenger. At that moment, Hanlan raised his head and flashed a smile at the champion. Trickett was shattered. Grabbing his oars, Hanlan gave a wave to the crowd and pulled away once more. In the final yards of the race, Hanlan was rowing consecutive strokes, first with his right oar, then with his left, as the boat zig-zagged toward the finish line. Cannons erupted, whistles blew, bells pealed for Hanlan. A very downcast Trickett slipped from sight, retiring to his quarters. It was reported that he took sick and refused to see anyone.

The Australians were a glum lot. Not only had their man lost the world title, but they had also spent so much money on the wagers that many did not have the fare necessary to return home. It was only through the quiet action of former Australians living in London that a fund was started to return the stranded to their homeland.

Edward Hanlan crushed Trickett for the World Championship. Muhammad Ali wasn’t the first athlete to show such superiority and be able to toy with his opponent. Why was Hanlan so determined to embarrass Trickett? It seems that Hanlan was incensed because Trickett and his friends were cocky and mocking him during training. —- So it goes.

The following year, 1881, Hanlan met Australian, Elias Laycock back on the Thames in London. Laycock insisted that clauses in their contract be included that forbade Hanlan from mocking him in the race or embarrassing him in any way. In a personal letter that I possess from Hanlan to Colonel Shaw while training for the match, Hanlan states that he’ll “make Mr. Laycock hop over this course [or] I am not Edward Hanlan”. Hanlan raced seriously, without incident and went on to win Easily.

Illustrated Londen News,

Bill Miller Collection

However, his rematch with Trickett in 1882 on the Thames followed the antics of the 1880 race. Hanlan played with Trickett during the race and then crossed the finish with almost a minute and a half lead. To add insult to injury, Hanlan turned his boat around and rowed down to Trickett, still on the racecourse, turned around again and beat him back to the finish a second time.

Hanlan went on to defend his World Champion title until August 16th, 1884, when Australian, William Beach, defeated him on the Parramatta River. For the next decade professional rowing slowly died because of the chicanery and the attention that other sports, such as baseball, were now commanding. By the turn of the century, professional rowing was history and the cheering crowds, the money wagered, and the superstar status of the scullers and oarsmen were mostly forgotten. —- So it goes.

Supplement to the Illustrated Sydney News, Aug. 27, 1884

19th Century rowing – immense popularity, huge crowds, vast sums of money, great excitement and many dirty tricks.

Books referenced:

- AMERICAN ROWING by Robert F. Kelley, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, NY, 1932

- ROWING & TRACK ATHLETICS by Samuel Crowthers and Arthur Ruhl, The Macmillan Co, NY, 1905

- THE HISTORY OF ROWING by Hylton Cleaver, Herbert Jenkins, London, 1957

- HARPER’S MONTHLY, December, 1869

- THE HARVARD H BOOK OF ATHLETICS, John A. Blanchard, 1923

- AQUATIC MONTHLY, ed. Peverelly, July 1872

- THE CANADIANS – NED HANLAN by Frank Cosentino, Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd. Ontario, 1978

- COURTNEY MASTER OARSMAN-CHAMPION COACH by Margaret K. Look, Empire State Book, NY, 1989